Artist unknown

Rack Picture for Dr. Nones, 1879

Art Institute of Chicago

William Michael Harnett [1848-1892]

The Letter Rack

The Faithful Colt John Haberle [1856-1933]

A Bachelor's Drawer (and 2 details)

The Slate

I recently did an invitation for the New-York Historical Society for an upcoming lecture called “Trompe L'oeil and Modernity” (see top image here, used on the invite). I'd link to the information but it is already sold out! (but I'm going!) My encore updated post here is very on point:

The book The Arts of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum by James W. Cook examines the curious strain in 19th century popular culture of illusionism (the self conscious aesthetic and cultural mode that "exists on the boundary between fact and fiction") and artful deception (which employs illusionism but purports to be real). Illusionism pervaded a range of 19th century entertainment, from Barnum's "humbugs," like the Feejee Mermaid, to Paul Phillipoteaux's Gettysburg Cyclorama, through all sorts of magic lantern displays, wax figures and sleights-of-hand. I imagine Cook could include the rage for seances, mediums and spirit images as well, though he doesn't go into these. In Cook's view, the public's passion for deceptive spectacle was influenced by the new "discourse" of advertising, social hierarchies and the expansion of the middle class, and the scientific inquiries of the time. Why was it though, that in a time of exacting definitions of propriety, when morality was strictly parsed and appearances were de facto comments on pedigree, society was thrilled by the questionable, and the ambiguous?

I was particularly interested in his chapter on trompe l'oeil painting--a genre which relied on spectacle. Numerous notices of the time described audiences that gathered to argue, gape at and dispute the nature of the paintings. Many of these paintings were run-away pop-cultural hits. Art critics of any standing, though, customarily dismissed trompe l'oeil work, likening it to the "curiosities" that garnered crowds at dime museums– vulgar and without merit. The work was easily employed in aesthetic and social judgments: if you like this stuff you are a philistine or a rube.

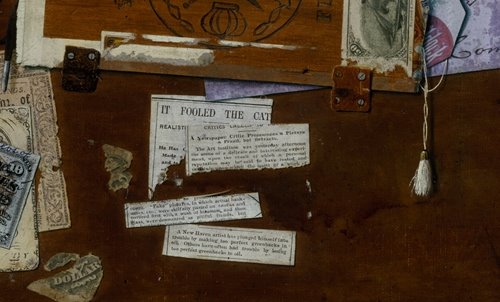

Harnett, Haberle, and Peto --three of the most successful trompe l'oeil painters–often used commercial packaging and other ephemera in their work (like the Dadaists would do literally 20-40 years later). But they were consummate nostalgia-peddlars (a pretty new idea at the time, the sentimental as cottage industry) who incorporated emblems of the West and cowboy life, Civil war paraphernalia, souvenir images of Lincoln, even recalling the good old days beside Grandma's Hearthstone. (Note that Haberle includes a "newsclipping" in his work The Bachelor's Drawer which purports to recount how Grandma's Hearthstone—his earlier painting!— was so convincing a cat curled up beside it's "fireplace"). These visual panoplies of the stuff of everyday life and the traditional home played to growing anxieties in contemporary 19th century society that modernity was erasing a way of life.

The heyday of trompe l'oeil was essentially contemporaneous with Impressionism, and a bit after. Most people think of latter as the aesthetic break-- edgy and avant garde while the former was populist and easily digested. An idea that intrigued me in the book was that trompe l'oeil, while not leading to Modernism, was never-the-less part of a changing visual mode. These sorts of perceptual 'experiments' lead to visual education and redefined the viewer as subjective participant. Visual doubt, essentially, (exemplified in these popular works) was part of the lead up to modernity.

Also worth noting is the fact that yesterday's avant garde (Impressionism) is today's greeting card art, while the overlooked populist work is the stuff of art historical criticism.

See also "I'd like to thank the Academy..." my post on Academic art and silent film.

No comments:

Post a Comment